In 1973, American wildlife was given hope for a sustainable future with the establishment of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The act was created to prevent the loss of endangered and threatened species and to preserve the places they live.

In the 50 years since the act was passed, we’ve seen remarkable stories of animal conservation. Species have made tremendous comebacks, and their habitats have been restored.

Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom is celebrating 50 years of the ESA and is proud to highlight endangered animal success stories on Wild Kingdom Protecting the Wild. Sharing stories of these vulnerable animals has been an important part of the series for more than 60 years.

Watch this public service announcement from Co-Hosts Peter Gros and Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant and keep reading to learn more.

How the Endangered Species Act began

Wildlife conservation began years before the ESA. Americans saw the decline of animals, such as bison and whooping cranes, as well as the extinction of passenger pigeons, and grew concerned as they watched familiar animals disappear. Early laws, such as the Lacey Act, put some regulations into place.

The Department of Interior made early steps toward the ESA in 1964 when it appointed the Committee on Rare and Endangered Wildlife Species. Then, in 1967, 14 mammals, 36 birds, three reptiles, three amphibians and 22 fish were named the first endangered species under the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966.

Momentum grew with the establishment of the Environment Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and more species were listed as endangered. The EPA outlawed DDT, a dangerous insecticide for both people and wildlife in 1972. That same year, Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Clean Water Act. President Richard Nixon called for Congress to enact comprehensive species legislation and in 1973, the landmark ESA passed, superseding earlier acts.

Why is the ESA hailed as landmark act? Unlike earlier legislation, the ESA isn’t limited to individual species or groups of animals. It’s for all species of fish, wildlife and plants. Finally, they could all receive equal protection.

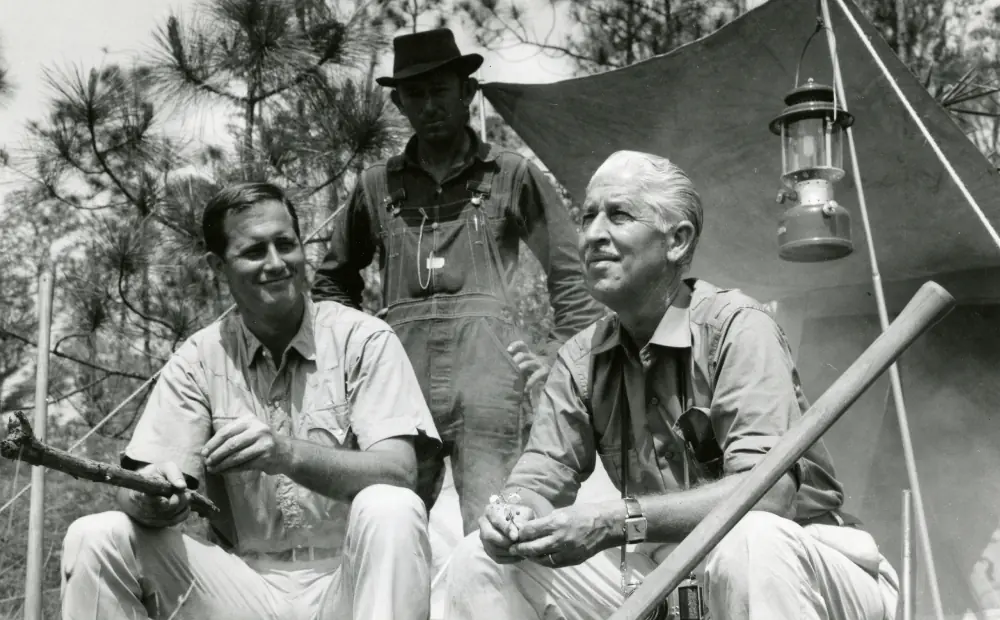

Marlin Perkins and the Endangered Species Act

As the ESA was put into law, a Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom host jumped in to help. Marlin Perkins and his wife, Carol, wrote letters of support and Marlin did interviews and PSAs to further publicize the act.

Then, in 1974, Marlin and the Wild Canid Survival and Research Center (now known as the Endangered Wolf Center) hosted the Symposium of Endangered and Threatened Species in North America in Washington, D.C. Representatives from numerous conservation organizations, as well as biologists from the U.S., Canada and Mexico, joined senate, congressional and federal government staff.

“This was the first time all the lobbyists from conservation organizations had ever spent a lot of time together and shared information with each other,” Marguerite Perkins Garrick, Marlin’s daughter said.

The event created alliances among policymakers and conservation groups, who shared upcoming legislation and garnered support from one another.

“Luckily this group was in place when the ESA came up for reauthorization in 1977 because there was a fierce movement by mostly western and southern members of Congress to eliminate if not the whole act at least Section 7,” Marguerite said. “This section forbade construction of federal projects without an environmental impact statement to make sure a critically endangered species would not be harmed.”

The coalition of conservation groups banded together to save the ESA, including Section 7, allowing today’s species to continue to receive protection.

Endangered Species Act species on Wild Kingdom

Just how successful is the ESA? Extinction has been prevented for 99% of species listed as endangered or threatened. In both the classic series and Wild Kingdom Protecting the Wild, our co-hosts have encountered many of these endangered species and have even seen some come off the list! Here are a few of our favorite stories.

Loggerhead turtle

1978 — listed as threatened

In Episode 3 of Protecting the Wild, “Sea Creatures of the Florida Coast,” Peter traveled to Florida to visit sea turtles, including the loggerhead turtle. These giant turtles are threatened by loss of habitat, vessel strikes and unintended capture in fishing gear. In the episode, Peter sees loggerheads in rehabilitation at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium and even witnesses a turtle’s release back into the wild.

But this wasn’t the first time Peter encountered loggerhead turtles with Wild Kingdom. Season 25, Episode 11, “Return of the Giant Loggerheads,” features Peter in 1987 on Heron Island, off the shore of Australia, where he discovered the work being done to preserve loggerheads.

Channel Island fox

2004 — listed as endangered

2016 — delisted due to recovery

Protecting the Wild Episode 6, “The Lost Fox of Channel Islands,” brought Peter and Dr. Rae off the coast of California to see a conservation success story. At one time, there were only 30 foxes remaining on the island. Today, the species is off the list thanks to the help of many conservationists and breeding programs.

Black-footed ferret

1967 — listed as endangered

Black-footed ferrets were listed as endangered species under early legislation and were grandfathered into the ESA in 1973. These animals were once thought to be completely extinct, but were rediscovered in Wyoming in 1981, launching the Black-Footed Ferret Recovery Program.

In an upcoming episode of Protecting the Wild, you’ll see the remarkable success story of black-footed ferrets as Dr. Rae and Peter travel to Wyoming, Colorado and California to learn about conservation efforts.

Bald eagle

1967 — listed as endangered

2007 — delisted due to recovery

America’s bird, the bald eagle, was once listed as an endangered species. Today, they are once again found across many parts of North America. Watch a remarkable story of a bald eagle’s recovery in an upcoming episode of Protecting the Wild.

Photo credit: NPS / Olin Feuerbacher

Devils Hole pupfish

1967 — listed as endangered

The world’s most endangered fish lives in an unusual place — Death Valley, California. The Devils Hole pupfish are only found in a deep cave in Death Valley National Park. But the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service are working to restore this critical species with a replica of the pond, home to captive-bred pupfish.

Watch this story in an upcoming episode of Protecting the Wild.

Sea otter

1977 — listed as threatened

Sea otters are a keystone species, critical to saving the kelp ecosystem. Hunted in the 1700s and 1800s and facing habitat challenges, the sea otters have never returned to their historic population.

However, scientists are recreating ideal habitats in the wild and healing orphaned and injured otters, as you’ll see in an upcoming Protecting the Wild episode.

Get a glimpse of how far sea otters have come by watching Season 12, Episode 1, “World of the Sea Otter,” where you’ll see Marlin visit otters from California to Alaska in 1973.

Peregrine falcon

1970 — listed as endangered

1999 — delisted due to recovery

The population of peregrine falcons declined, largely in part to DDT. Conservation organizations and federal agencies cooperated to release more than 6,000 American peregrine falcons since 1974. These falcons were rescued from extinction thanks to captive breeding and the protection from the ESA.

In Season 17, Episode 7, “Return of the Falcon,” Wild Kingdom co-hosts journeyed to areas where the falcon had become extinct. If only they knew the falcon’s great fate awaiting them!

Today, peregrine falcons even call Mutual of Omaha headquarters home, one of the only sites where you’ll find these falcons in Nebraska.

Whooping crane

1967 — listed as endangered

North America’s tallest bird, the whooping crane, once ranged across the U.S., but today only exists at three locations in the wild. Captive breeding programs are helping reintroduce the species, and today, there are 535 whooping cranes in the wild and captivity.

Whooping cranes are featured among other endangered species in Season 21, Episode 9, “The Unique Partnership.” In 1983, Marlin explored the partnership between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, universities, state fish and game agencies and private organizations like the Wildlife Management Institute.

Wondering how to help protect endangered species? You don’t need to be a conservation scientist to make a difference. Learn 10 ways to save endangered species.